Hospital homicide? Medical records show Texas girl died from a hospital-acquired pneumonia superbug — NOT measles

04/10/2025 / By Willow Tohi

- An 8-year-old girl, Daisy Hildebrand, died in Texas after being diagnosed with measles, but medical experts later attributed her death to hospital-acquired pneumonia caused by antibiotic-resistant E. coli, compounded by medical errors.

- Critical mistakes included stopping antibiotics too soon, administering high-dose steroids without anti-infectives, delaying a sputum culture and using an incorrect antibiotic (ceftazidime) when the infection required imipenem.

- The case reignited discussions on measles vaccine safety and efficacy. While vaccines reduced measles cases, concerns persist over waning immunity (60% of vaccinated children remain susceptible to subclinical infection) and side effects (febrile seizures, autism correlation in some studies).

- Some experts, like Mary Holland of Children’s Health Defense, advocate for single measles vaccines over the MMR, arguing natural infection may confer better immunity with fewer risks than vaccination.

- Daisy’s death underscores the need for better medical protocols, transparency in vaccine safety research and a balanced approach to public health that addresses both treatment errors and vaccination concerns.

In a recent development that has sparked intense debate, the death of 8-year-old Daisy Hildebrand in West Texas has brought the issue of measles and its treatment into the spotlight. The Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) initially reported that Daisy died from “measles pulmonary failure.” However, a detailed analysis of her medical records by leading medical experts suggests that her death was more likely due to hospital-acquired pneumonia, a condition that was exacerbated by a series of medical errors.

The case of Daisy Hildebrand

Daisy Hildebrand was admitted to University Medical Center (UMC) Children’s Hospital in Lubbock, Texas, on March 21, with community-acquired pneumonia, a urinary tract infection and dehydration. She tested positive for measles on March 24 and was treated with antibiotics and oxygen. After showing signs of improvement, she was discharged on March 24. However, her condition deteriorated, and she was readmitted to UMC on March 27 with a high fever, cough and shortness of breath.

Dr. Pierre Kory, a pulmonologist and critical care specialist, reviewed Daisy’s medical records and concluded that her death was due to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) secondary to hospital-acquired pneumonia. Kory noted that the causative organism was a highly antibiotic-resistant E. coli, which she likely contracted during her first ICU stay.

Medical errors and treatment failures

Kory highlighted several critical errors in Daisy’s treatment that may have contributed to her death:

- Lack of antibiotics: Despite her worsening condition, antibiotics were stopped early in her second hospital stay. Kory stated, “The admitting doctor’s diagnosis was ‘pneumonitis,’ and antibiotics were quickly stopped after admission.”

- High-dose steroids without anti-infectives: The hospital staff administered high-dose steroids without pairing them with appropriate anti-infectives, which Kory described as a “lousy idea.”

- Delayed sputum culture: A sputum culture, which could have identified the specific bacteria causing her pneumonia, was not performed until days into her second stay. By the time the results came back, it was too late to change her treatment effectively.

- Incorrect antibiotic choice: On day seven of her second stay, the hospital staff broadened the antibiotic treatment to include ceftazidime. However, the E. coli causing her pneumonia was resistant to this antibiotic. Kory noted that the correct antibiotic, imipenem, was not administered.

Historical context and public health implications

The case of Daisy Hildebrand raises important questions about the treatment of measles and the broader implications for public health. Measles, once a common childhood illness, has been largely controlled in the U.S. through vaccination. However, the effectiveness and safety of the measles vaccine have been subjects of ongoing debate.

Measles mortality rates:

- Pre-vaccine era: Measles mortality rates had already declined significantly by the time the first measles vaccine was introduced in 1963. According to the CDC, the death rate from measles dropped by 98% from 1900 to 1955, largely due to improved sanitation and nutrition.

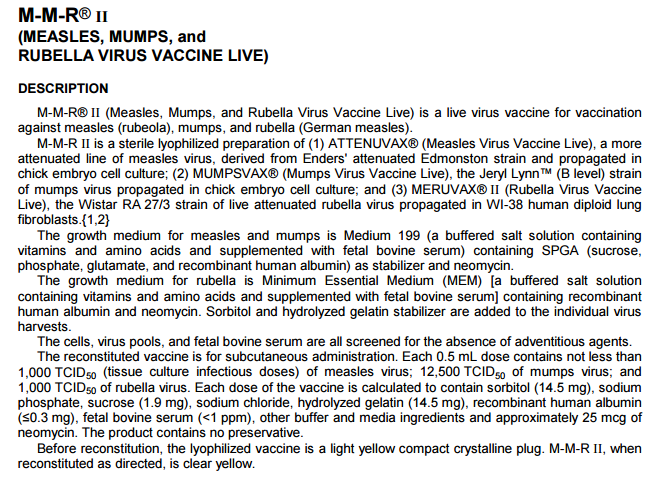

- Post-vaccine era: While the measles vaccine has further reduced the number of reported cases, concerns about vaccine safety and efficacy persist. The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) has recorded 144 deaths following MMR or MMRV vaccination between 2000 and 2024, compared to nine measles-related deaths reported to the CDC during the same period.

Vaccine safety and efficacy:

- Waning immunity: Research shows that immunity from the measles vaccine wanes over time, with about 60% of vaccinated children susceptible to subclinical measles infection and 33% of adults susceptible to clinical infection by age 24-26.

- Serious health risks: The MMR vaccine has been associated with serious health risks, including febrile seizures, anaphylaxis, meningitis, encephalitis, thrombocytopenia, arthralgia and vasculitis. A 2004 study found that boys vaccinated with their first MMR vaccine on time were 67% more likely to be diagnosed with autism compared to boys who received the vaccine after their third birthday.

The role of natural immunity

Proponents of natural immunity argue that contracting measles naturally provides more comprehensive and long-term immunity compared to the vaccine. While the illness can occasionally be serious, the risk of permanent injury and death from the MMR vaccine has not been proven to be less than that of measles itself.

Mary Holland, CEO of Children’s Health Defense (CHD), emphasized the importance of offering single measles shots as a safer alternative to the MMR vaccine. “If the Department of Health really wants to use a vaccine strategy to go after measles, then they should offer people a single measles shot. It would be safer than the MMR, which has proven to carry many serious risks.”

Conclusion

The death of Daisy Hildebrand serves as a stark reminder of the complexities and challenges in treating infectious diseases. While the measles vaccine has played a role in reducing the incidence of the disease, the case highlights the critical importance of proper medical care and the need for ongoing research into vaccine safety and efficacy. As the debate continues, it is crucial to balance public health measures with individual health concerns and to ensure that medical errors are identified and addressed to prevent similar tragedies in the future.

Sources include:

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

. vaccines, bad doctors, CDC, Fact Check, health care, hospital homicide, immune system, medical errors, Pneumonia, real investigations, superbug, truth, vaccine wars

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author