The gut-liver axis: A new front in the sweetener wars

02/05/2026 / By Willow Tohi

- New research reveals the common sugar-free sweetener sorbitol is metabolized into fructose in the liver, activating pathways linked to fatty liver disease.

- An individual’s gut microbiome is crucial; specific beneficial bacteria can break down sorbitol, but without them, it reaches the liver and is converted to fat.

- The study, using zebrafish models, found that high consumption of sorbitol or glucose can overwhelm even a healthy gut’s protective capacity.

- This challenges the long-held assumption that sugar alcohols like sorbitol are inert and harmless substitutes for regular sugar.

- The findings are particularly relevant for individuals with diabetes or metabolic conditions who may consume high levels of “sugar-free” products containing sorbitol.

In a discovery that upends decades of dietary dogma, scientists at Washington University in St. Louis have uncovered a direct and alarming link between sorbitol—a ubiquitous “sugar-free” sweetener—and the development of fatty liver disease. Published in the journal Science Signaling in late 2025, the research provides compelling evidence that this popular sugar alcohol is not the inert substance once believed. Instead, it can be metabolized into fructose within the liver, hijacking the same harmful metabolic pathways as regular sugar. The critical determinant of risk, the study reveals, lies within an individual’s unique gut microbiome, turning a simple dietary swap into a complex biological gamble.

From innocent substitute to metabolic saboteur

For over half a century, sugar alcohols like sorbitol have been heralded as safe havens in the storm of sugar consumption. Marketed as low-calorie, tooth-friendly and diabetic-safe alternatives, they became staples in everything from diet soda and sugar-free gum to “keto-friendly” snacks. The prevailing assumption was that they passed through the body largely unabsorbed, offering sweetness without consequence. This new research dismantles that simplicity. The Washington University team, led by nutrition researcher Gary Patti, demonstrated that sorbitol is anything but inert. Using sophisticated isotope tracing in zebrafish, they mapped its journey: when protective gut bacteria are absent or overwhelmed, sorbitol travels directly to the liver. There, it is converted into a fructose derivative, a compound proven to drive the liver’s overproduction and storage of fat—the hallmark of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD).

The microbiome: Your personal gatekeeper

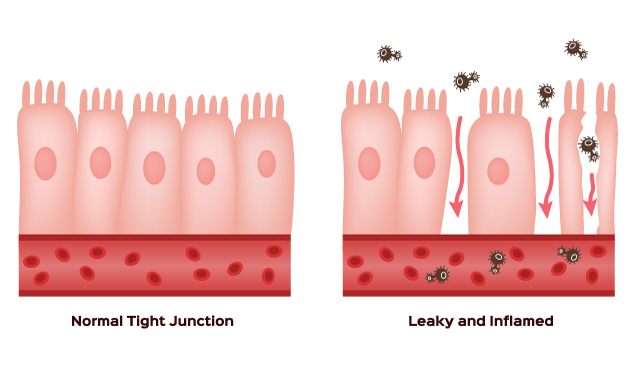

The study’s most significant insight is the pivotal role of the gut microbiome. The researchers identified specific beneficial bacteria, such as Aeromonas strains, capable of degrading sorbitol into harmless byproducts before it ever reaches the liver. This acts as a natural protective barrier. However, in individuals lacking these bacterial populations—a state known as gut dysbiosis—this gatekeeping function fails. The team found that zebrafish with depleted microbiomes had fifteen times more sorbitol-derived fructose in their livers than those with intact gut flora. This finding personalizes the risk, suggesting that the health impact of a “sugar-free” candy is not universal but depends on the microscopic ecosystem within one’s digestive tract.

When even a healthy gut is overwhelmed

The protection offered by gut bacteria has its limits. The research indicates a dose-dependent danger. While a modest amount of sorbitol, such as that naturally occurring in fruits, can be efficiently cleared by robust gut flora, the modern diet presents a double threat. Consuming large quantities of dietary sorbitol from processed foods, or even high levels of glucose which the gut can convert into sorbitol, can swamp the system. The beneficial bacteria become overwhelmed, allowing sorbitol to slip past the intestinal gate and flood the liver. This creates a paradoxical scenario where consuming large amounts of either sugar or its “healthier” alternative can converge on the same damaging metabolic outcome in the liver.

Rethinking “free” in sugar-free

This research forces a historical reconsideration of the “diet” and “sugar-free” movements that gained momentum in the late 20th century. Driven by fears of sugar, obesity and diabetes, the food industry and consumers alike embraced artificial sweeteners as a guilt-free solution. Sorbitol, derived from corn syrup, became a workhorse of this revolution. The new findings suggest this swap may have inadvertently traded one set of metabolic problems for another, contributing to the silent global epidemic of MASLD, which now affects approximately 30% of adults worldwide. It underscores a growing principle in nutritional science: there is rarely a “free lunch” when tricking the body’s ancient sensing mechanisms for sweetness.

A converging path to metabolic health

The revelation about sorbitol is more than an indictment of a single additive; it is a clarion call for a more nuanced understanding of diet and metabolism. It highlights the liver’s vulnerability to fructose, regardless of whether it comes directly from table sugar, high-fructose corn syrup, or is synthesized internally from a supposed safe substitute. For individuals, particularly those with existing metabolic conditions like diabetes who may heavily rely on sugar-free products, the advice is shifting from simple substitution to mindful reduction. The ultimate conclusion from this groundbreaking work is that the path to metabolic health appears less about finding clever sugar replacements and more about moderating overall sweetness, fostering a diverse gut microbiome and recognizing the complex, interconnected pathways where food is translated into function—or dysfunction—within the human body.

Sources for this article include:

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

Censored Science, dangerous ingredients, food supply, grocery, gut health, liver health, microbiome, research, sorbitol, stop eating poison, sugar alcohols, sugar-free, sweetener, toxins

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author